There’s a famous story about an executive that hired Edward W. Deming to spend a week with his team and offer recommendations on how to improve both their own performance and the performance of the organization they led. Word has it that Deming arrived on the first day, said “hello,” and then walked straight to the corner of the executive’s office to sit down. He stayed there, sitting silently for the entire day as the executive went about his daily activities.

At the end of the day, the executive approach Deming and asked “Do you have any thoughts?” All Deming said was, “I’ll be back tomorrow,” and he walked out the door.

The next day—just as he had the day before—Deming walked into the executive’s office, sat in the corner, and said nothing. He did scribble a few notes from time to time as the executive went about his daily activities. Again, at the end of the day, the executive asked Deming for his thoughts. Again, Deming simply said, “I’ll be back tomorrow.”

This cycle continued throughout the entire week until Friday evening when the executive lost patience and pushed Deming for a more informative answer. Deming asked him one question: “What are the top three priorities for the business?” The executive rolled them off like a shot. “Well,” said Deming, “you’ve spent the entire week working on none of them, yet your time has been entirely booked, and every conversation with you and every conversation with every individual that walks into your office starts with how busy you are. Can you guess why?”

We all love being busy. In fact, we celebrate and subtly enjoying telling our colleagues, collaborators, and competitors how “busy” we are. The question we don’t consider is this: What is the cost of all this busy-ness?

In the majority of organizations, being “busy” is systemic, and often for perverse reasons. Being visibly busy is often seen as or at least equated to hard work, real work, important work. Yes, being visibly and easily observed as busy by constantly running around from meeting to meeting, short on time with places to go and people to see signifies credibility of hard, committed work. In many cases, people are rewarded for it—further propagating the hero culture of <insert name> working late nights, evenings, and weekends to get us over the line. It becomes the drug to keep and reward the motion of the hamsters’ wheels as they keep spinning. But too often this spinning motion is mistaken for progress.

Believe me, it’s not.

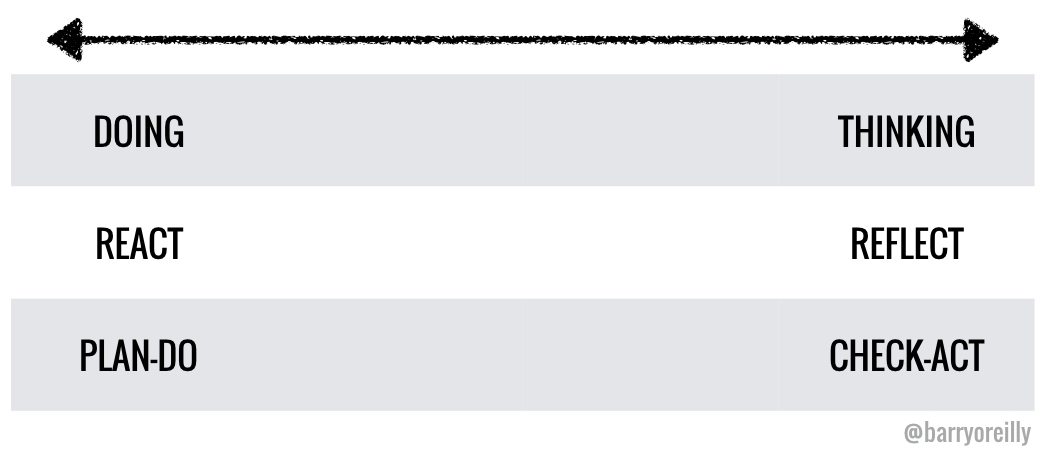

Over-optimizing for executing work is dangerous. Actually, it’s very dangerous indeed as it causes us to get stuck in plan-do-plan-do cycles. We compromise reflection, retrospection, and review of the outcomes of all the output we are creating. We stop building learning loops into our work to plan-do-check-act the results of all this effort. We don’t allow time to study, consider, or understand if the result of all this activity is actually aligned to what we are hoping to achieve. We are frankly too busy to.

Stop (And Think)

I find myself constantly reminding people that thinking is an activity too. Yet how much time to you really make for it? If I was to go through your schedule for the week, where would I see it? When would it happen?

In Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow by Daniel Kahneman, we are told that we essentially have two modes of thinking before acting, known as System 1 and System 2. System 1 is our reactive, speedy response to circumstance decision-making. It is a bias loaded, preprogrammed neural network of pathways that essentially exists so we don’t have to think. System 2, however, is when we deeply, slowly consider numerous situations, options, and alternatives when decision making.

Now, we obviously can’t use System 2 for every decision we have to make, or we would get nowhere. Similarly, only using System 1 the entire time means we are in danger of making snap decisions full of false assumptions based on incomplete information or little evidence. The point to be aware of is this: if you are over-optimizing and not balancing these modes of thinking—and, in turn, decision-making—you are likely to end up in a less than desirable state.

I challenge leaders to consistently make time for System 2 thinking during the course of their workday. It’s an imperative, not only important. The trick to achieve this is to consider the decisions that need to be made. Know what they will require and be deliberate about when to use either mode.

Make time to reflect, to retrospect, and decide next steps or corrective actions that need to be made. Define the information you need to make those decisions, then seek out, absorb and process it. When you over-optimize for “doing,” you lose the power of “thinking.” We need to do both for effective decision making while still allowing the organization to move at speed.

One exercise I get leaders to do is mark where they think they are on each aspect of the above three continuums. You might surprise—even scare—yourself when you do it.

Collaborate

More often than not, we cannot make every decision on our own—as much as we might like to! Making time to coordinate with colleagues is important, especially when delivering complex and interdependent initiatives. However, how much time do you make for debate and alignment, both unplanned and planned, with your collaborators?

It’s not uncommon for me to see executives and leadership teams that are unable to “get time” with one another for weeks out into the future. The side effect of this symptom is further queuing of work and delayed decision-making. When you fill your plate to the maximum, you’re removing opportunity or showing no empathy for the people you need to collaborate with. Expecting them to drop everything they are doing and report to your office is a form of disrespect. Further still, if you’re setting this example of behavior with your reports, you can be sure the same behavior will trickle down to theirs.

Making time and space for planned and unplanned collaboration is important, especially if you want your organization to move fast at scale. It’s easy to say “I empower my teams to make decisions,” but in truth they can’t, don’t, or won’t want to make every decision in isolation.

And Listen…

Be sure to find time to listen to what your people are discovering through the course of their work, to inform and improve your own decision-making. Free space to allow timely support for collaboration and communication with the people you rely on—especially for when the unexpected but expected happens!

Try creating a Vanilla Ice calendar with a lotted time to stop (and think), collaborate and listen.. Yo! V.I.P let’s kick it

Remember, our most valuable commodity as leaders is time. What are we spending it on, who are we spending it with, and how do we use it to achieve the outcomes we desire? If you’re in the business of being busy, I’d suggest you get out of it before you and your organization become busy to death.

Things to consider:

- Have a list of your top priorities. If what you’re being ask to do isn’t on it, then don’t do it, or alternatively suggest how people can move ahead without you.

- Thinking is an activity too—don’t undervalue it. Make time and space for it in your daily work schedule (not evenings and weekends).

- Stop booking all your available capacity. It means you’ve no adaptability or optionality in your schedule for unexpected events (which should be expected to happen).

- Use an activity account to understand where you are spending your time. It doesn’t have to be overly sophisticated. Look at last week’s calendar and write down notes about each day

- Set relative percentages for where you want to spend your time, then track and monitor it. If it’s not what you want, think of how you can adapt how you spend your time to move toward it.